The Uncertain Future of Carmakers

Lifting up the hood or sliding beneath a Tesla reveals that the car is missing many of the keystone parts we normally associate with automobiles. Things like transmissions.

The transmission, a box that includes five or more gears to ensure smooth acceleration in a normal gasoline-powered vehicle, simply doesn’t exist in an electric car. It's unneeded, effectively replaced by electronics and software—a fate befalling more of our cars’ mechanical guts.

Future car mechanics won't need to know how to teardown and rebuild a transmission, but they may need a degree in electrical engineering or computer science. And car owners of the future may not need to know how to drive, as cars will do that on their own better than humans ever have.

As complicated mechanical parts are replaced by simpler parts that can be finely controlled by software, the balance of power will continue to shift away from incumbent carmakers whose software expertise, while not trivial, isn't superior to startups in Silicon Valley or elsewhere. Couple that with the effect of self-driving cars, which will most certainly lead to fewer cars being sold as vehicles are commoditized as a fungible resource, and the question becomes: will the incumbent carmakers survive — and if so, how?

Some prominent tech minds believe that traditional carmakers are already doomed. But it's unlikely that Ford, GM, Toyota, Honda and the rest of them will all disappear. Some of the winners of the next chapter of transportation will be companies of which we haven’t yet heard. But some of the incumbents will find ways to adapt, to evolve.

Apple evolved by turning into a phone company and staying at the forefront of the market for its new product. Hewlett-Packard, however, has been stuck, having missed opportunities to define trends, be they in mobile, cloud computing or new generations of devices. The car business, as it morphs into a technology business, may be even more unforgiving for incumbents, as it may well be a shrinking business.

Many people still don't see this coming

I recently talked about this topic in front of a crowd at technology-focused event in St. Louis with Express Scripts CIO Neil Sample (formerly CTO of eBay). The audience was fairly educated on the latest movements and trends in technology. But when we did a quick poll of the crowd on their impressions of self-driving cars, a majority of them didn't believe the product would make a huge impact in our lives anytime in the next 15 years. Most of the audience was skeptical that cars driven by algorithms would ever have a big impact.

For those who run in tight circles of people who work in tech, this may be surprising. But most people don't work in tech, don't live in Silicon Valley and haven't ridden in one of Uber's self-driving Volvos that the city of Pittsburgh successfully lured to their streets.

People don't see this coming. As has become clearer during the last several months, there exists a palpable divide on how people view the world in this country—and this topic is no exception.

A September 2016 survey from Kelley Blue Book revealed some interesting takeaways that show the size of the gap between where technologists think the car market is going and what most people think/prefer.

Out of 2,264 polled people, from 12-64 years old:

- 80% thought people should always have the option to drive, to control the vehicle

- 64% said 'I need to be in control of my vehicle'

- 62% said they loved to drive and driving seems fun

- 62% said they preferred to drive when in any vehicle

Perhaps most surprising, only 49% of respondents said that they would surrender/agree to less control of their vehicles even if they knew that it meant roads would be safer overall. The other 51% said they preferred retaining 100% control of their vehicle, even if it's not as safe for other people on the road.

But there were things in the survey that pointed to a growing acceptance of autonomous cars:

- 63% of people think roadways would be safer if autonomous vehicles were standard—yet, as evinced by the point above, people still don’t want to surrender their keys

- Only 37% of people think roadways would be safer if all vehicles were operated by people

Some of this divide breaks purely down generational lines. People in their twenties are more likely to live in urban areas now compared with a generation ago, and the shift in their attitudes toward cards, compared with earlier generations, has been documented.

Self-driving cars, of course, fit into the sharing economy trend, something that's been more quickly embraced by younger people who not only utilize it as consumers, but also by those who make it part of their own earning economy. The fact that this generation's wealth will only increase during the next decade as it ages and becomes a mainstay of the economy will help smooth the transition to self-driving cars and the shared networks they enable.

The car market will be smaller

There still exists a gap between the average price per mile of owning a car versus the per mile price of traveling with services like Uber or traditional taxis. It's cheaper, overall, to own and operate one’s own vehicle, assuming a nominal amount of miles are driven. But that gap will disappear with the advent of autonomous ride-sharing vehicles, according to data and estimates from EverCharge, which makes rapid charging systems for electric cars.

The breakdown:

- Traditional Vehicle Ownership: $0.70 - $1.50 a mile

- Taxi Cab: $2.80 - $6 a mile

- Ride-Hailing Service (Uber/Lyft): $1.40 - $3.00 a mile

- Autonomous vehicles with a ride-hailing or sharing: ~$1.00 a mile

Autonomous vehicles combined with ride-hailing or sharing will flatten the market. Those who choose to eschew buying or leasing a car can skip worrying about parking, garage space and insurance. For many, this will align lifestyle choices with economics, giving people the freedom and quality of life they prefer while not costing them extra money to get around—a powerful lever.

With fewer cars doing more work, automakers will find it difficult to retain and grow share in a shrinking market. The model of building cars and simply waiting for consumers to show up and buy them will be relegated to a smaller and smaller piece of the overall vehicle market.

Carmakers will need to court and develop new markets for their cars.

Their survival will hinge on two things:

-

Being able to place their vehicles into ride-sharing fleets owned by companies such as Uber, or by the car companies themselves. But carmakers have not yet fully embraced this paradigm, although reports indicate that GM may have bid on Lyft, of which it owns 9%.

-

Automakers’ ability to develop or acquire technology that keeps pace in what will be a rapid march toward full-autonomy and vehicles that are fused products of software and hardware. The thinking here is that automakers’ success will depend on the ability to buy the right companies at the right moments.

Carmakers need to get electric: the car fleets in dense, richer developed cities could be 40% battery-powered within 15 years.

It's cities such as London, Chicago, Singapore and Tokyo, where there already exists a healthy web of clean mass transit and a ready base of dense infrastructure and population, where EVs will become prominent first.

At this point, there aren't enough EVs and they simply aren't cheap enough to have a large effect on the overall car market. Tesla prices start at more than $70,000; Nissan's Leaf is $30,000; BMW's i3 is $42,000; and Chevrolet's Volt is $33,000. But those prices are dropping. Tesla's model 3, which has drawn 400,000 reservations, will change the demographics of the customers the California company reaches. Other carmakers efforts aren't far behind—they may even be a step ahead.

The prices of components required to make electric cars are quickly dropping as the technology becomes better and more commoditized. The price of large, efficient lithium-ion batteries dropped 65% between 2010 and 2015, from $1,000/kWh to $350/kWh, and they are forecast to drop below $100/kWh within the decade.

McKinsey forecasts that the cost of owning an electric car will be equal or below that of driving a car powered by combustible fuel by the mid 2020s. The last 50 years of EV development has all been pointed at this moment.

Tightening emissions standards put in place by governments will further press the EV movement along, as carmakers will be required to continue increasing their fleets' efficiencies with respect to gasoline. All of these forces will coalesce to rapidly increase the numbers of EVs on our roads, a hardware development that will greatly enable the rise and role of software in vehicles.

Current carmakers' advantages are shrinking

As the software that's paired with cars becomes more complicated, the cars themselves, the mechanical marvels that move us from place to place, grow less complicated. As cars' physical components become simpler, the moats that exist around auto production get smaller and smaller.

"The rapid shift to software-based vehicles guts the technological advantages the automotive industry has enjoyed for a hundred years," says Richard Switzer, a senior strategist at The Working Group, a Canadian software consultancy. "Electric cars are pretty much a big battery and an electric motor, neither of which the big automakers enjoy any competitive advantage in supplying or manufacturing."

With autonomous cars entering the market in the not-too-distant future, Switzer sees subscription-type models of car ownership, obviating car ownership for a significant part of the market as long as they can deliver the two things that car owners primarily value: comfort and convenience.

The advantages of self-navigation and productive travel time, along with the elimination of parking hassles, will drive a rapid adoption of autonomous technology. Reconfiguring revenue models and allowing for vastly different business approaches will be a requirement for any carmaker to thrive.

"It will be interesting to see which traditional carmaker is the first to commit their own resources to this type of model," Switzer adds.

Carmakers must continue their pivot into software, and keep acquiring companies

Large carmakers' survival depends on being nimble and wily, not something for which they’re known.

"Redirecting a large industrial company like a car company is like turning a ship. It’s hard to do quickly but it can be done. Look at how successfully GE has shifted to digital," says Dave Edwards, a co-founder at Intelligetsia.ai, a research firm focused on AI, robots, and cars.

Edwards thinks that it's imperative that carmakers' software efforts are in-step with other major segments of their businesses, and that they form a core discipline for the company. That means acquisitions of software companies have to be knitted in to be part of the parent company's DNA, helping it evolve and adapt to the changing industry. Software company acquisitions that are operated within their own silos will not help car companies survive.

Traditional car companies still hold trump cards, and sit behind some barriers to entry that can give them an edge.

Those include:

- Political clout to affect legislation and regulations—something that's affected Tesla's go-to market in many states

- Investment capital to build, own, and operate fleets

- Manufacturing capability to build all the new cars

"The technology will never get on the road without the rest of the car. While nimbleness may have a lot of sex appeal, it’s important to remember that industrial products require investment, planning, and experience," Edwards explains.

Japanese automakers surprised Detroit in the 1970s and 1980s by building smaller, more efficient cars that consumers did in fact want. American companies failed to see this demand, and therefore failed to deliver this set of products. The entire industry now, in the United States, Europe, Japan, Korea and elsewhere, must take developing trends seriously, or risk a quick fall to irrelevance.

Those in Silicon Valley expect that automakers will continue to look to software companies, either through partnerships or acquisitions, to get the expertise required in the evolving vehicle market.

Ross Mason, the technical co-founder of MuleSoft, which makes integration software for APIs and disparate cloud platforms with clients such as Tesla, Audi and BMW, frames it as a question: Will Uber figure out how to build cars before GM figures out how to build software?

"Everyone, including Google, Ford, Apple, GM, Tesla, Lyft, Microsoft, Toyota and Uber, want to own the car platform to ultimately own the passenger experience," Mason says. "Silicon Valley natives really know how to build software, and car manufacturers really know how to build cars. The key lies in combining manufactured cars with intuitive, smart software to offer consumers the experiences and services they want or, even better, don’t know they want until they have them."

Software expertise will be critical for automakers as some parts of their revenue models will shift away from the one-time sales of cars into different kinds of streaming payments.

Josh Siegel, a PhD at MIT who is researching connected vehicles, says that the winning car companies will branch into offering convenience services and experiences as product differentiators. Consumers will make car-buying decisions based on software, not just hardware.

As autonomous vehicles free drivers' cognitive facilities from the task of driving, vehicle occupants will be able to focus on other things. This will allow manufacturers to monetize advertising, media consumption and a panoply of other possibilities within the car.

"Car companies will have to shift their business models from revolving primarily around the sale of durable goods to one emphasizing experiences and services," Siegel says.

But the market makeover from one that emphasizes a single large transaction, often financed, to one that's more durable and steady, like a subscription, may look very different in different places. Shared vehicles running solely on electricity empowered by automated driving bots will be far more prevalent in wealthier urban areas early on, predicts McKinsey.

The sharing economy will not be able to overcome the benefits of private vehicles for those who live in more suburban and rural areas. It is in the exact places where the freedom of private automobiles has enabled sprawl and spread that will largely still require private cars decades into the future.

Even so, there are more people moving into dense megacities each year. More than 60% of the world's population will reside in these places by 2060, where a shared network of autonomous cars makes sense. Knowing this, car companies won't risk being complacent—nor will those companies, like Uber, who look to challenge the current paradigm.

Uber felt its own efforts to produce better autonomous driving technology was moving too slowly, so last year it raided Carnegie Mellon University for 40 researchers and professors who specialize in robotics, almost forcing the school's National Robotics Engineering Center to close its doors.

Ford, also sensing the intensity of this race, declared in August 2016 that it plans to offer mass-produced, fully autonomous vehicles by 2021, available with no steering wheel or controls—so as to make rides more comfortable for passengers. Ford says it plans to reach its goal through a combination of collaboration with tech companies and startups, and doubling the size of its Silicon Valley team.

Hiring in Silicon Valley is great, but it may take more than that, points out Joseph Nagle, Evercharge's director of marketing. "Many of the core competencies needed for the autonomous vehicle do not reside (currently) within the Big 3 or the big international players," he says.

GM, for instance, rapidly advanced its own place in the race for autonomy with its $1 billion acquisition of Cruise, a Y Combinator company focused on creating software to power self-driving cars.

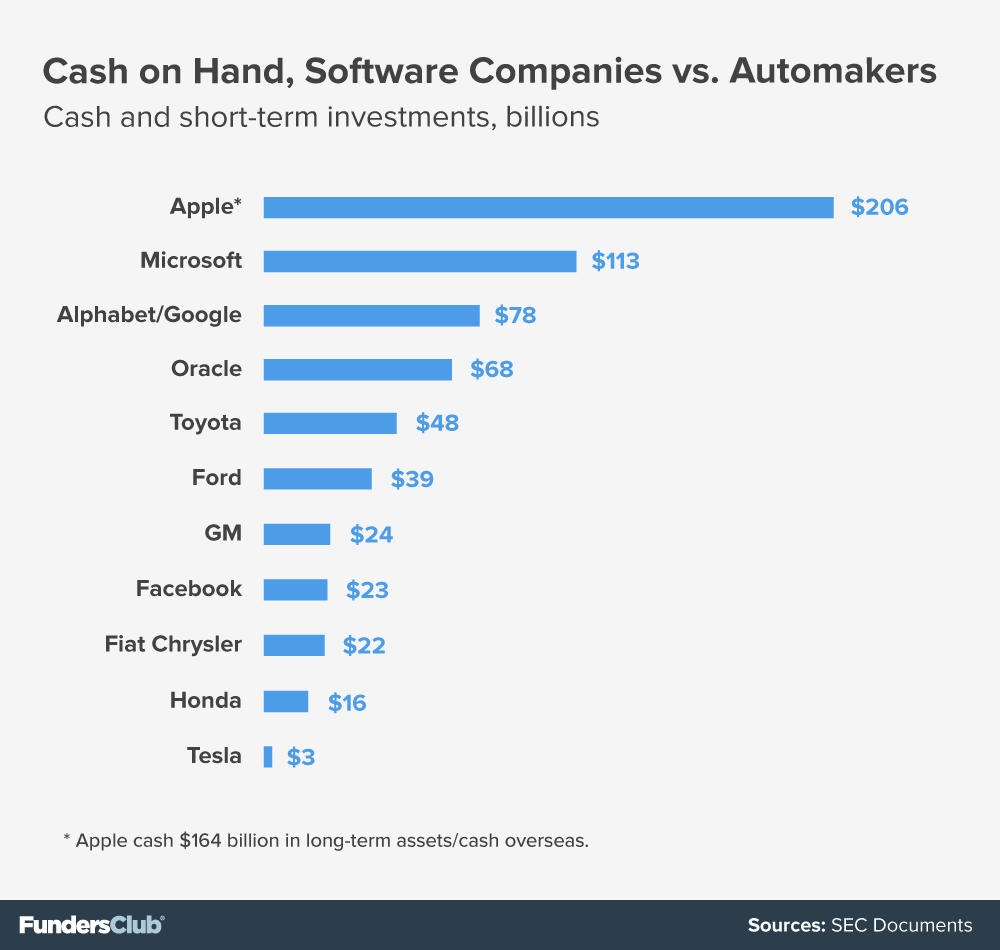

This surely won't be GM's last acquisition in the space. And Ford, with more ready cash than all carmakers other than Toyota, may be the next to make a move to buttress its proclamations around autonomous cars:

Cash and short-term investments:

- Ford: $39 billion

- GM: $24 billion

- Fiat Chrysler: $22 billion

- Toyota: $48 billion

- Honda: $15.6 billion

- Tesla: $3.2 billion

But It may be the carmakers who get acquired by software companies, rather than the other way around.

Winners of the coming car wars will need to emulate Apple, mixing a mastery of hardware and software to stand out from a field of very similar products. Apple and Google both see that cars form the next big software platform. These are the companies that were cagey enough to have effectively split the mobile market. Neither will want to cede the vehicular one.

Likewise, other software companies who perhaps missed nailing mobile in the same way will be bent on beating rivals in the car market. Facebook, Microsoft and Amazon will all monitor the space closely. And there's no reason to think that companies such as Oracle, SAP and Salesforce won't look to get their software into company fleet and shipping vehicles in an effort to win umbrella ERPs.

"Based on the market capitalization of the Googles, Apples and Ubers of the world, as well as their stake in the Internet of Things, which includes cars, I would expect the automakers to be the ones being bought, not the other way around," asserts John Dinsmore, a business professor at Wright State University who closely monitors the tech side of the car business.

The balance sheets of tech companies, then, may prove more interesting than those of the carmakers, as there are many companies who could theoretically make a big acquisition in the space. The cash piles, including short-term investments, on hand at the alpha tech companies are well larger than those at carmakers:

Cash and short-term investments:

- Alphabet/Google: $78 billion

- Apple: $42 billion ($164 billion in long-term assets/cash overseas)

- Microsoft: $113 billion

- Facebook: $23 billion

- Oracle: $68 billion

Summary

It’s unlikely that all of the carmakers as we now know them will survive cars’ next major evolution. It’s remarkable that the big three American carmakers have survived as they have for so long, in some form or another.

The difference now is that there exist other, better capitalized companies which are bent on owning large portions of the space in the coming decades. Apple and Google have been relatively secretive about their efforts, but they’re clearly focused on not surrendering the gains both companies made while dominating the mobile market.

Apple, for one, could buy GM or Ford and still have more than $100 billion of cash left to fund whatever it saw fit. And that’s at today’s prices, when car companies are doing relatively well and possess strong balance sheets. A downturn in the economy, a slowdown in car buying, could change everything; it could be the precipitate needed for upheaval in what has been one of the most steady businesses in the United States across a century.

The automakers must scour the technology sector for the right people, the right technologies and the right companies whose assimilation may keep them competitive into the future. Waiting for technologies or companies to mature would be a mistake. By then, valuations for the new tech will be out of reach.

If this were simply about building vehicles, then the incumbents would have a pronounced edge. But the electrification of cars and the invasion of software and self-driving platforms has negated automakers’ advantages. They’re now playing on an even field, at best, with the best and richest technology companies on the planet.

Many people and companies didn’t see how big the shift to mobile was until it was upon us. That lesson is recent enough that car companies are wittingly cognizant of it. But that may not be enough.